Some thoughts on spaced repetition

Disclaimer: This is just a collection of my thoughts, I haven't tried too hard to source everything or verify what I say, partly because That's Hard, and partly because I'm trying to get across my intuitions as someone who has vaguely tried to use spaced repetition a bit and has read some blog posts.

Spaced repetition is often touted as the solution to many of the ills of the education system and, for its most vocal proponents, a way of life. There are plenty of studies showing that it 'works' in a narrow sense, but it's still not widely used, not in mainstream education, and not that much anywhere else either. When it is used it is still mostly for exam-preparation (boring) or 'party-trick' type memorising. There are some non-critical explanations available for why it hasn't caught on: maybe people are just lazy, or they don't really want to learn, they want to signal that they are learning. But the lore of spaced repetition in its current form has been around for a good decade or two now, and as time goes on it becomes harder to support such explanations. If spaced repetition really did speed up your ability to learn things by 2x or 10x we would by now be seeing that many or most people in positions that require you to have learned a lot of stuff are heavy users of spaced repetition, this is not what we see1. I have some non-non-critical explanations to offer, and some other general thoughts.

What (narrowly) spaced repetition works for

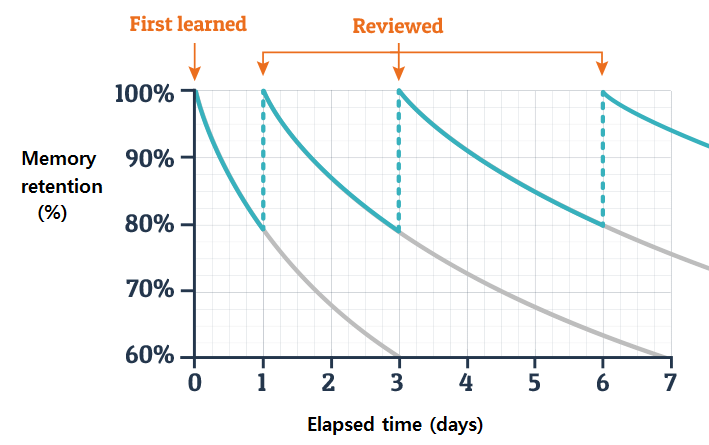

The basic premise of spaced repetition is that when you study something, the degree to which you remember it2 decays as an exponential curve (the forgetting curve). Studying for longer in one session doesn't have any effect once you have reached Maximum Remembering so you should wait until you have Forgotten It A Bit and then review what you learned. Each time you do this the exponential curve gets shallower so you can wait longer before reviewing again.

These basic ideas were established by Hermann Ebbinghaus (around 1900 maybe), who 'discovered' the exponential nature of the forgetting curve by trying to memorise 'nonsense syllables' (e.g. KAJ, BOK) and measuring how many of them he could remember over time. I'm sure more research has been done since then, maybe some of it has built on this in a meaningful way, but if just you read around blogs and stuff this is basically the 'theory' of spaced repetition.

I'm going to take all this sort of research as basically sound (because it probably is, and because it doesn't make much difference to this post), so we know that a very good way to memorise random syllables is to space out review sessions over exponentially increasing time intervals, and that this also works for many other specific cases that have been studied.

Some general criticisms

Memorising random syllables is an example of a domain in which the things you learn are easy to understand but hard to remember. The set of syllables is well defined and doesn't change so you can just look at the same flashcard over and over again until you remember it. The easy-hard dichotomy suggests that there are four such classes, let's address them all one by one:

Easy to understand, easy to remember (EUER)

Here things are easy all round so everything's hunky dory and you don't need any special technique to help you. An example of this is remembering faces. You understand immediately where someones eyes are or that they've got a big nose. And once you've seen someone a couple of times you will recognise them for years.

Easy to understand, hard to remember (EUHR)

As mentioned above this is where spaced repetition really shines. "Learning the names of things" is a class of examples (e.g. all the bones in the human body, all the countries in Europe). There's nothing really "to understand" about the fact that your big leg bone is called a femur in english, you just need to remember it. These sort of key-value pairs are necessary for a lot of exams, and for bootstrapping some other skills (e.g. learning a language) but many people (me) see this kind of learning as shallow and best avoided.

If you don't need to take an exam you can just look up the names of things when you need to, and if you are using this one-one technique to memorise a lot of specific but related things (e.g. how to factorise a quadratic, how to complete the square on a quadratic, how to apply the quadratic formula) it can be a sign that you are missing out on some more general understanding that will save you a lot of time.

Hard to understand, easy to remember (HUER)

An example of this is riding a bike, this is a domain in which spaced repetition is not that helpful, each gradual improvement in ability is hard to achieve, but once you do achieve it it's not going anywhere, so by the time you understand something well enough to turn it into a flashcard (or equivalent spaced-repitition-able artifact3) you are not going to forget it anyway.

Incidentally I think this class of skill are by far the most valuable in life because once you have paid the upfront cost of learning the thing you can reap the rewards for the rest of your life. You are the intellectual landlord (but good) rather than the intellectual renter. I also think that, going back to the quadratic equations, many things can be either EUHR or HUER depending on how you think about them. Chopping a subject like quadratic equations up into small pieces that can be memorised makes it seem less daunting (easier to teach in schools) but you end up with a set of isolated facts that are hard to remember, and no appreciation of what the point of all of it was.

Hard to understand, hard to remember (HUHR)

This domain is implied by the easy-hard dichotomy but I'm having a hard time coming up with a good example. I think that's because being hard to understand tends to make something easy to remember (this observation is worth its own post). One possible set of examples are theories that are actually wrong, or incomplete in some way. For example if you try and learn the details of the theory of luminiferous ether that was broadly speaking accepted at the start of the 20th century you find that it's more complicated than special relativity (the correct theory) turned out to be, and harder to remember because a few of the logical steps don't quite make sense.

Well that was a fun little analysis, time to regroup. I seem to have decided that being hard to remember is a bit of a red flag, it either means what you're learning isn't formulated in the simplest way, or that it's actually wrong. And also that cutting things up into small reviewable pieces can be a dangerous habit to get into because it does not always scale towards a general understanding.

What (broadly) I think spaced repetition works and doesn't work for

Based on this analysis we can think about some specific things that spaced repetition probably works for (there may also be actual studies about some of these), some of these have been mentioned already:

- Studying for exams, but particularly for things where there is not a natural structure to the content, e.g. it might work better for History, where there are a lot of random dates and things to remember, that it does for maths.

- "Bootstrapping" certain skills (learning the basics so it's easier to make progress/understand what people are talking about). For example you could have a flashcard for each musical note, or for the 100 most common words in a language. You need to know these things to get a foothold, but the flashcard approach doesn't make sense once you're trying to compose a symphony, or have an actual conversation with someone.

- Maybe working in a domain where the Theory hasn't been quite worked out yet, so the bag of facts approach is still the best way to go, e.g. our current understanding of dark matter is just a bundle of observations that suggest there is more matter in the universe than we can see. Developing "a deep understanding" of dark matter would require you to know what it is

I don't however think that it works for trying to become genuinely effective in a field, e.g. becoming a productive programmer, or a great musician, or an academic who publishes high quality papers. It may help in some specific areas with all these things but they all require a complex and intuitive model of what you're working with and I don't think spaced repetition will get you there any faster (because these things are in the hard to understand easy to remember category) and it may actually make you worse by getting you bogged down in the details.

This whole post's been a bit of a dunk on spaced repetition but I'm just trying to push against the some of the stronger claims of it being a life changing innovation because I used to be credulous of these claims. I will still use it to study for exams and stuff. Also the idea of spacing things out at all (even if you don't flashcard and track everything) is a valuable insight that I use every day.

Footnotes

- (1) Some alternative explanations for this are:

- learning a lot of stuff is not as widely useful as you might think

- these people are overrepresented but they keep it secret

I don't think either of these are true

- (2) In a broad sense, or as the percentage of flashcards that you remember

- (3) So far I seem to have conflated "flashcard apps" with "spaced repetition" so you could make the valid criticism that spaced repetition refers to a broader category of techniques that are more effective than what I have described. For example if you are learning a language you could give yourself a challenge to "talk to someone about the weather" at increasing intervals until you can do it fluently. This is true and I think that sort of thing could be useful but it is also true that most people who are "into spaced repetition" just use flash card apps.